Civil society organisations claimed a landmark victory against fossil fuel power in South Africa on December 4 when the High Court in Pretoria turned down the national government’s plan to add more coal-fired power stations to the country’s power grid. According to the court, the government’s plan was “inconsistent with the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa” and thus unlawful.

The ‘Cancel Coal’ case

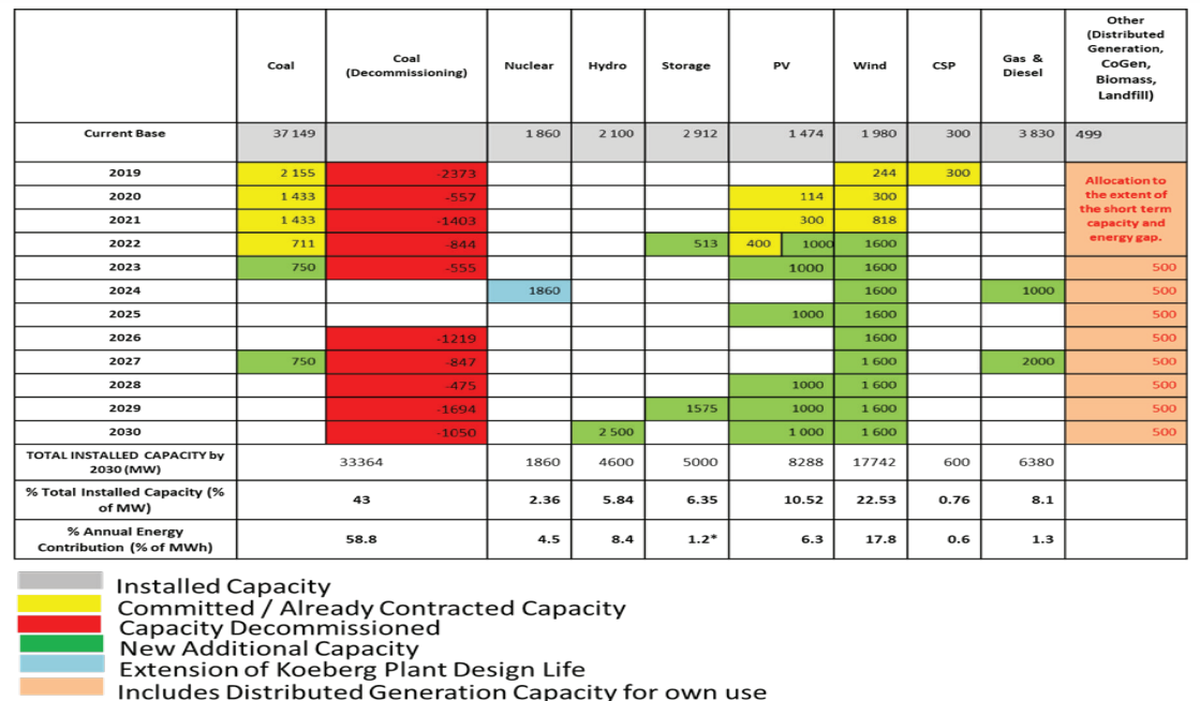

In its Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), the government of South Africa announced in October 2019 that it plans to add 1,500 MW of coal power to the country’s national grid – 750 MW by 2023 and another 750 MW by 2027.

IRP 2019

| Photo Credit:

Government of South Africa

The Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and the National Energy Regulator of South Africa in 2020 backed the announcement.

In 2021, youth-led civil organisations including the African Climate Alliance, the Vukani Environmental Justice Movement in Action, and the Groundwork Trust, represented by the Centre for Environmental Rights, brought the case against the government’s plan. The group alleged that the plan would harm the environment and cause health issues, especially among children. The case soon acquired the popular monicker “Cancel Coal”.

South Africa’s energy mix

Like most economically developing nations, South Africa is heavily dependent on coal for its energy needs. According to estimates by the International Energy Agency, almost 71% of the country’s total energy supply came from coal power in 2022.

According to an analysis of global emissions through history by Climate Watch, South Africa is the world’s 16th largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

South Africa has ratified the Paris Agreement, which means it is legally bound to cut its greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to mitigating global warming. According to the Nationally Determined Contributions South Africa submitted in 2021, the country plans to cut 350-420 million tonnes of carbon-dioxide-equivalent (MtCO2e) of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. It has also committed to reaching net-zero by 2050.

In July 2024, the country’s President Cyril Ramaphosa signed the Climate Change Act into law, which includes a clause to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Details of the judgement

Civil society organisations contended that the government’s plan to add more coal power didn’t consider the rights of children as granted by the Constitution of South Africa.

According to the Constitution, South African citizens have the right “to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations”. This is to be ensured through measures that “prevent pollution and ecological degradation, promote conservation, secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development.”

The court ruled that the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and the National Energy Regulator couldn’t provide enough evidence to show that the ill effects of the coal power on the environment and the health of the people, especially children, had been considered, suggesting they didn’t “comply with their constitutional obligations”.

Speaking to The Hindu, Ritwick Dutta, environmental justice lawyer and associate of Doughty Street Chambers U.K., said the order is a significant development in the field of climate litigation.

“Although, at the core, the judgment still follows the basic principles of administrative law – duty to give reasons and non–application of mind to relevant consideration – what is however significant is the fact that the court held that the minister, while according approval, did not take into account the interest of the future generations or the unborn generations.”

He also highlighted the fact that “since the Court relied on Section 28 of the South African Constitution, which requires the state to protect the child against ‘neglect and degradation’ to hold that the governments/minsters decision was not in the ‘best interest of the child’. The implication of this judgment as I see it is the requirement that a minister/government decision must not be based on the immediate short-term need but must consider a long-term holistic view,” Mr. Dutta said.

A 2019 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health reviewed epidemiological the literature to understand the impact of coal-fired power plant emissions on children’s health. It concluded that they affect children negatively due to their “developing physiology, anatomy, metabolism, and health behaviours”. The review also observed that children who lived near a coal-fired plant exhibited more asthma and respiratory-related conditions.

Environmental justice

The case is also an example of environmental justice in the context of transitioning away from coal worldwide.

“Even in India, for the first time three ministries – Ministry of Power, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change and the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy – jointly filed an affidavit before the Supreme Court in the case of M.K Ranjitsingh versus Union of India that India will have to move from polluting coal to wind and solar not only to ensure cleaner air but also to meet its commitment under the Paris Agreement,” Mr. Dutta said. “Coal will continue to meet the energy requirement in the short run, but it is now accepted that transition is a must if the world has to slow down climate change. The fact that courts globally are recognising this reality is … only natural.”

The lawyer also said that even though this case is limited to coal power, combating climate crisis goes beyond it. “Judicial decisions on climate change are a recognition of both the urgency to deal with climate crisis and the fact that civil society groups and citizens have an important role to play in tackling the crisis. It should not be forgotten that the South African judgement is an outcome of litigation undertaken by three civil society groups. It is therefore crucial that the state and the judiciary are more open and receptive towards divergent views on dealing with the crisis of an unparalleled nature,” he added.

Published – December 26, 2024 07:37 am IST